10 facts about strange names in ancient Rome

He began to read about how people were called in ancient Rome, and was very impressed. Compared with them, everything is very simple in our world today (even if we take into account Russian patronymic names).

The theme of these names is extensive, and you can dig around for a very long time - naming traditions have changed over a millennium and a half, and each genus has its own quirks and customs. But I tried and simplified all this for you in ten interesting points. I think you will like it.

The classic name of the Roman citizen consisted of three parts:

A personal name, "name", was given by parents. It is similar to today's names.

The name of the genus, "nomen" is something like our surnames. Belonging to an old noble family meant a lot.

An individual nickname, "cognomogeneous," was often given to a person for some merit (not necessarily good) or inherited.

For example, the most famous Roman, Guy Julius Caesar, had Guy, nomen - Julius, and cognomen - Caesar. At the same time, he inherited all three parts of his name from his father and grandfather, whom both were named in exactly the same way - Gaius Julius Caesar. So Julius is not a name at all, but rather a surname!

In general, the eldest son's inheritance of all the names of his father was a tradition. Thus, he also adopted the status and titles of the parent, continuing his work. The rest of the sons, as a rule, were given other names so as not to confuse the children. Often they were called in the same way as father's brothers.

But bother only with the first four sons. If there were more of them, then the rest were simply called by number: Quintus (fifth), Sextus (sixth), Septimus (seventh), etc.

As a result, due to the continuation of this practice for many years, the number of popular pre-names narrowed from 72 to a small group of repeated names: Decim, Guy, Caeson, Lucius, Mark, Publius, Servius and Titus were so popular that they were usually reduced to just the first letter. Everyone immediately understood what they were talking about.

The society of ancient Rome was clearly divided into plebeians and patricians. And although there were sometimes cases when families of distinguished plebeians achieved the status of aristocrats, adoption of a noble family was a much more frequent method of social growth.

Usually this was done in order to extend the family of an influential person, which means that the adopted child had to accept the name of the new parent. At the same time, his previous name turned into a nickname-cognomogenous, sometimes in addition to the existing cognomnates of the adoptive father.

So, Guy Julius Caesar adopted in his testament a grand-nephew, Guy Octavius Fury, and he, having changed his name, began to be called Guy Julius Caesar Octavian. (Later, as he seized power, he added a few more titles and nicknames).

If a person did not inherit the cognitive from his father, then he spent the first years of his life without him until he distinguished himself from his relatives.

In the era of the late Republic, people often chose out-of-fashion prenomes as cognomans. For example, at the dawn of the Roman state, there was the popular name Agrippa. Gradually, its popularity faded away, but the name was revived as cognitive among some influential families at the end of the republican period.

The successful cognomance was fixed for many generations, creating a new branch in the genus - this was the case with Caesar in the genus Juliev. Each family also had its own traditions on the topic of which Congnomes were appropriated by its members.

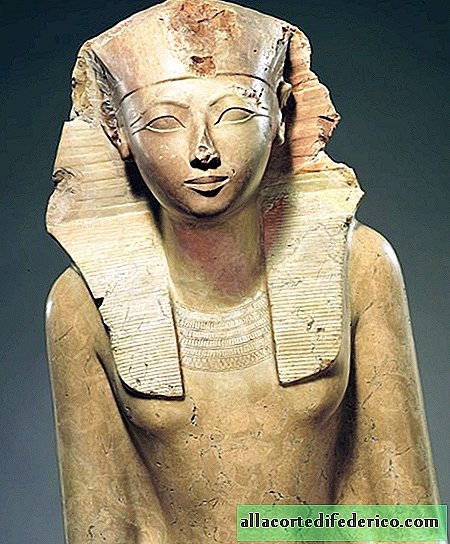

All Roman names had male and female forms. This extended not only to personal prenomes, but also to surnames-nomen and nicknames-cognomains. For example, all women from the Julia clan were called Julia, and those who had Agrippa's cognomism were called Agrippins.

When marrying, the woman did not take the nomen of her husband, so it was difficult to confuse her with other family members.

But personal names, prenomens, were rarely used in women of the late Republic. And the cognom too. Perhaps this was due to the fact that women did not take part in the public life of Rome, so there was no need to distinguish them from strangers. Be that as it may, most often, even in noble families, daughters were called simply the female form of their father’s nomen.

That is, all the women in the genus Juliev were Julia. Parents just had to call their daughter, but others did not need it (until she got married). And if the family had two daughters, then they were called Julia the Elder and Julia the Younger. If three, then Prima, Second and Thirds. Sometimes the eldest daughter could be called Maxim.

When a foreigner acquired Roman citizenship (usually at the end of military service), he usually accepted the name of his patron, or, if he was a freed slave, the name of his former master.

During the period of the Roman Empire, there were many cases when a huge number of people immediately became citizens by imperial decree. By tradition, they all took the name of the emperor, which caused considerable embarrassment.

For example, the Edict of Caracalla (this emperor got his cognognism from the name of the Gallic clothes - a long robe, the fashion for which he introduced) made the citizens of Rome all free people in its vast territory. And all these new Romans adopted the imperial nomen Aurelius. Of course, after such actions the meaning of these names was greatly reduced.

Imperial names are generally something special. The longer the emperor lived and ruled, the more names he typed. Basically it was the cognomen and their late variety, the agnomen.

For example, the full name of the emperor Claudius was Tiberius Claudius Caesar Augustus Germanicus.

Over time, Caesar Augustus has become not so much a name as a title - it was accepted by those who sought imperial power.

Beginning in the early empire, prenomes began to lose popularity and were largely replaced by cognomains. This was partly due to the fact that there were few pre-names in everyday life (see paragraph 2), and family traditions increasingly dictated the name of all sons to the pre-name of the father. Thus, from generation to generation, premenom and nomen remained the same, gradually turning into a complex "surname".

At the same time, it was possible to roam the Congnome, and after the 1st - 2nd centuries of our era, it was they who became real names in our understanding.

Starting from the 3rd century AD, the domain and nomen were generally used less and less. This was partly due to the fact that a lot of people with the same nomenclature appeared in the empire - people who received citizenship in large numbers as a result of an imperial decree (see paragraph 7), and their descendants.

Since cognitive became by this time a more individual name, people preferred to use it.

The last documented use of the Roman nomen was at the beginning of the 7th century.